The Neurodiverse Brain: Parenting Kids With Autism

“My oldest was a really difficult baby,” Christi Tom says. “She was meeting major milestones, but, looking back, she was behind socially with peers and her sensory issues interfered with sleeping and eating.”

Tom says that loud noises such as automatic toilets, blenders, vacuums and hand dryers were terrifying and overwhelming. Tom’s daughter also had what she calls “big emotions” that she had trouble regulating.

Getting a Diagnosis

Feeling in her gut that something was wrong, and suspecting autism, Tom began to ask questions, but was told her daughter didn’t have the typical signs of autism.

“She wasn’t meeting the checklist,” Tom says. “She was speaking. She was very verbal, but not able to communicate what she wanted. She would make eye contact with people she knew well.”

Still in the process of seeking help, Tom says that her daughter was treated for sensory issues, but not autism.

Tom finally sought an evaluation with a DIR Certified Occupational Therapost. “It’s a very neurodiverse-positive model,” Tom says. The therapist met with her before evaluating her daughter, and then spent an hour observing her daughter play. Ultimately, Tom’s daughter did get an autism spectrum disorder diagnosis.

Autism spectrum disorder is defined by the National Institute of Mental Health as “a neurological and developmental disorder that affects how people interact with others, communicate, learn, and behave.” Individuals with autism range from those having severe limitations to those who are highly functional.

“Autism is underdiagnosed in girls,” says Ed Callahan, Ph.D., and owner of Neurodiversity University.* Callahan coaches parents on the best ways to work with their neurodiverse child, teen or young adult. “As a society, we haven’t been trained to look at it. Girls are better at masking.” Callahan also says that girls often focus on neurotypical interests, but the intensity level is higher than their neurotypical peers.

Ed Callahan, Ph.D., with Neurodiversity University, has expertise in effective parenting for neurodiverse children and teens.

Both of Tom’s daughters have been diagnosed with autism and ADHD, but are also gifted, which can make diagnosis more difficult. It is not uncommon for individuals with autism to have other disorders such as ADHD.

Signs

Daniel Nelson, a child and adolescent psychiatrist and medical director for the Child Psychiatry Unit at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, says that autism begins in utero, although the exact cause is unknown. He says that the bioposy of a brain with autism will show structural disorganization. “We don’t know why it happens,” he says. “It could be a neurodevelopmental variant, an environmental cause, and autism can run in families, so there can be a genetic component.” He is quick to point out that childhood vaccines do not cause autism.

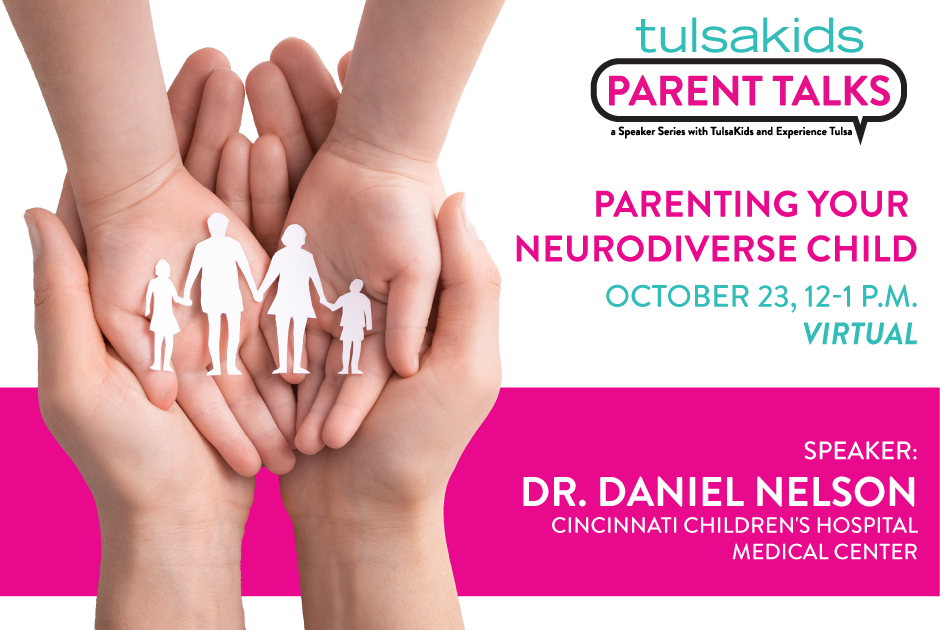

Daniel Nelson, MD, is the medical director for the Child Psychiatry Unit at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center

Tom noted a genetic component in her own family and in her ex-husband’s family.

Dr. Nelson says, for that reason, doctors should always ask for a family history. “Whatever illnesses run in the family are more likely to be expressed,” he says.

Signs that parents can look for, according to Nelson, include lack of “molding” and unusual emotional reactions. “Infants typically mold to your body when you pick them up. With these kids, it’s like holding a board,” he says. “They can freak out at textures or being held. Very subtle changes can cause them to become upset. For example, if you move the ottoman in your living room, and the kid comes in and it doesn’t look right, the kid will scream. You move the furniture back, and it’s like a flipped switch and they’re fine.”

Kids with autism may also violate social norms. “We don’t ask permission to sit in a chair, but we wouldn’t just sit in someone’s lap,” Nelson says. “They may do unsusual social things.” He described a recent patient whose mom bought him a book about insects and butterflies. “He was smart in his understanding of butterflies,” Nelson says, “but that’s all he talked about. They don’t recognize their own feelings and don’t recognize the feelings of others.

Other signs include:

- Developmental and psycho-social delays (not getting along with other kids).

- An inability to understand their feelings or the feelings of others. Dr. Nelson described how individuals with autism will learn to do things like smile at another person to make the person feel comfortable, even though they see no reason to smile.

- A lack of reciprocity. As early as 7 months, kids flip from being OK with everybody, to recognizing strangers. Kids with autism may not experience that. They may be indifferent to people.

- Intense focus on one thing, such as drawing or cars. “Sometimes there’s an obsessive quality to it,” Nelson says. “They may want to watch the same Disney movie over and over for 10 hours a day every day.”

- Delayed speech.

- Limited eye contact.

- Lack of social skills. They may think very literally.

- Sensory issues. Light, noise, textures bother them.

- Difficulty with transitions or shifting from one task to another. Dr. Callahan, who works with parents of adolescents, says that autism may not show up until kids are transitioning to middle school when social pressure and the need for higher-level executive function gets more complex. “That’s when the challenges start to show up,” he says. “They may be able to hold it together to get by and do well at school, but they come home and can’t hold it together.”

- Difficulty with changes in routine or schedules. “That’s why meltdowns are pretty common,” Callahan says. “They’ve put together a whole plan on how the day’s going to go. They process a situation by seeing the details first, while neurotypicals look at context first. It takes a lot of energy to do that. When one detail is changed, they have to rebuild the whole model.”

- Repetitive behaviors.

- Rigid thinking.

- Masking. As children get older, they may mask certain behaviors to fit in with peers. “They can act like everyone else and pretend to be other people,” Callahan says. “That takes a toll on their self-esteem, and the energy it takes to blend in can be exhausting.”

How do you know if it’s a problem? Callahan says to look at the spectrum and the circumstances where problems occur. Do they have problems with friends, food sensitivities, hyper-focused interests, coordination issues, dyslexia or dysgraphia?

“Some kids (with autism) can be very social and play sports,” Callahan says. “They can look OK at school, but when they get home, they fall apart. They may be honest to a fault because it’s hard for them to not tell the truth. They may misinterpret situations.”

While there are overarching similarities, each child is unique.

Finding Help and Accommodations

Not every child has every behavior. What works for one child may not work for another. Both Nelson and Callahan say that it’s important for parents to seek professional help if they have concerns about their child. Don’t try to self-diagnose.

Nelson says to find a professional who will listen to you and work with you as a partner in diagnosis and treatment. “I tell parents that I work with, ‘look, I don’t know your child as well as you do. You know them far better, but I’ve seen thousands of these cases, and I want to share information with you, and you can share your information with me.’ The interaction between doctor and patient should be mutually enjoyable.”

Parents have a legal right to ask public schools for an evaluation if a disability is suspected, but schools also have budget pressures, so it may take time. Callahan urges parents to be proactive and push for testing and accommodations, if necessary.

Tom, who is a newly trained occupational therapist, advises starting early. She suggests getting a SoonerStart developmental assessment if you have concerns in the first year of life. “Follow your gut if you see signs,” she says. “Getting services can take a long time. Keep asking questions.” Tom also recommends keeping notes of “quirks” that you observe in your child, so you have it ready when you see a doctor or therapist.

Understanding what your child needs and communicating with teachers can help neurodivergent children succeed in school. For example, Tom says her teacher put a Post-It over the automatic flusher, so the noise wouldn’t bother her daughter. Kids who have trouble following several directions at once may need to have fewer directions. Visual calendars, untimed tests, movement breaks, quiet times and predictable routines help her girls.

“Slow the process and break it down,” Callahan says. “I call it leaving breadcrumbs. Give them time to process a change because the initial response will be resistant. Parents have to know how to advocate for their neurodivergent kid.”

Tom says that it helps to show up at school; get to know the teacher and the aid. Communicate about the diagnosis so they can help provide what your child needs.

Parenting: “Goodness of Fit”

Healthy parenting, whether with a neurotypical or neurodivergent child, is the same, Nelson says. Healthy parents provide structure and set firm, consistent, predictable and reasonable limits without being overly strict.

“Kids love predictability,” he says.

Tom uses predictable systems, and she recognizes when her girls need extra help.

“Recognize that you know your kid best,” Tom says. “Understand what overwhelms your kid, what stresses them, what triggers behaviors, what helps them cope or calm down. Sometimes when I think they’re not listening or being frustrating, I do side by side coaching. Neurodiverse kids may be behind a few years, so giving them multiple steps may be overwhelming.”

Nelson says such awareness is important. “The best type of parenting is ‘Goodness of Fit’,” he says. “Kids have different needs, so reasonable limits may be different for certain kids. Expectations for a child who doesn’t have challenges may be different from expectations of a child who does have challenges. For example, a child with a high aggressive index will need more restriction. If they’re hitting other kids at preschool, they’ll need more redirection.”

Callahan advises parents to hold boundaries, but also recognize the reasons behind meltdowns. “Punishments don’t work well,” he says. “It has to be logical to the kid. Solve problems together. Help them find and maximize their strengths, while working on their challenges. Their brain is working differently, so our solutions may not be the right ones for them.”

While it may be tempting to allow your neurodivergent child to focus on one thing obsessively all day, it won’t help their development. Instead, you might use the obsession as a reward. “If you indulge it full tilt, all of a sudden, you’ve created a monster,” Nelson says. “Games like Minecraft and Roblox grab autistic kids. They’re addictive to the autistic brain. I would recommend against letting a kid do it more than an hour or two a day. Beyond that, you’ve eaten up all their learning time.”

Nelson says that neurodiverse and neurotypical people can meet halfway. The world needs to be more accepting and accommodating, but neurodiverse kids also need to understand that there are a lot of things we don’t love doing, but will make life easier.

“Parenting is that way,” he says. “Get our shoes on, get in the car seat, etc. If you let kids – any kid — do only the stuff they want to do, they won’t learn. A child who is challenged can get over hurdles with a little help and they can do a lot of things. If they don’t get help, they can get overwhelmed and they may think, ‘I’m damaged’ and ‘why would anyone like me?’ There is a balance between getting some of the things you love and getting up, putting your clothes on and going to school.”

“If parents can understand one thing,” Callahan says, “it’s that neurodiverse kids’ brains work differently. Make room for them in the world and understand that a certain part of the population operates differently. Find ways to approach gently because the world can feel pretty hostile to them already.” Callahan also urges parents to manage their own emotions.

Working with adolescents and young adults means helping them prepare. “Have them manage their own money,” Callahan says. “Do laundry.” He uses the “I do, we do, you do” method of showing them a few times, then doing it along with them, and then having them do the task on their own.

Tom knows firsthand that a parent “can’t pour from an empty cup.” Ask for help and communicate with others. And communicate with your neurodiverse child. “My goal is for my kids to know themselves, their strengths and weaknesses and to understand the supports they need…to advocate for themselves so they can be capable and confident in a world that is not made with them in mind.”

Nelson encourages parents to learn what normal, healthy development looks like and then get expert help if they need it. “Always go ask for help when you have a feeling that something is wrong.”

*If you’d like to contact Dr. Ed Callahan, please reach out to him directly at 801.201.7164 or learn more at neurodiversity-u.com