Life Isn’t Always Fair: The Sibling Perspective of Disabilities

Last week, when I was having lunch with my brother, a wave of sadness and anger washed over me. There was nothing particularly wrong that day. We were at my brother’s favorite place to eat, and I was going through my usual routine of preparing his coffee, monitoring his food intake, and attempting to make pleasant chatter as he inhaled his food. It was a typical outing for us, but for some reason, a painful emotion shoved its unwelcome head into my thoughts. I felt cheated and angry. I questioned God and the universe. After spending sixty years as a sibling to a brother with intellectual disabilities, you’d think I would have landed in the acceptance stage. For the most part, I have, but every once in a blue moon, I regress to the anger stage. I’m angry that life isn’t fair for my brother.

Society wants us to smile and pretend we wouldn’t change a thing, but I would change a lot to make life easier for my brother. It’s not always acceptable to be honest, but honesty is a necessity for me. I speak my truth, but that doesn’t mean it’s a universal truth. Every family and situation has their own personal truth, which might be completely different from mine. I don’t presume to speak for anyone else.

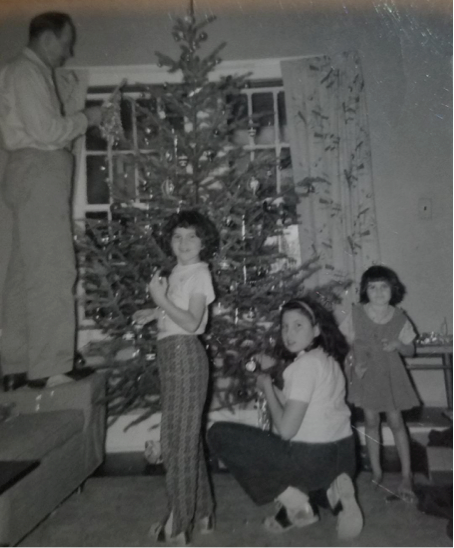

When David was born, he appeared to be a healthy baby, passing all the Apgar tests and looking “normal.” My mother started suspecting something was wrong when my brother began missing the developmental milestones at the same timeline as her previous three children, but doctors dismissed her concerns. Even after the doctors grudgingly diagnosed him with “mental retardation” at the age of three, it was easy for us to pretend he wasn’t. His disabilities were invisible, and I might be a little biased, but he was pretty adorable. David had auburn hair, bright blue eyes, and freckles across his face. Unless someone tried to speak with him, he could “pass” as neurotypical.

David began exhibiting self-harm tendencies and aggression toward others around the age of five. I remember fending off his fists and laughing about it when we were young. The laughing stopped as he became older and stronger. The aggressive behavior became more challenging to control. He developed callouses on his hand from where he bit his hand in frustration, often bringing blood to the surface. Yet we mostly ignored it, making occasional ineffective attempts to curtail his head banging, hand biting, and hitting others.

As he got older, his differences became more noticeable. My brother was changing. David was no longer the cute little boy, and the world responded differently to him. It seems that most people are accepting of others with disabilities as long as it comes in a pretty package. Most people accept the person with mild disabilities, especially if they have the facial features we associate with “special needs.” We embrace the person with minimal demands who can be presented publicly as homecoming royalty to make us feel better about ourselves. That way, we can pat ourselves on the back as having done our good deed and not let our minds be troubled by the problems people with disabilities must face the other 364 days of the year.

It gets more complicated. Parents age and die, leaving the person with disabilities alone, in alternative living facilities, or in the care of siblings. The stage of life after the parents die is rarely addressed, as if remaining in denial will prevent it from happening. No one wants to talk about what happens to the adult with disabilities after their parents die.

The world isn’t always a kind and accepting place. Family members of people with disabilities must develop thick skin while retaining an open and loving heart. We must constantly advocate and protect while not letting it make us bitter and resentful. I like to think I hit that balance most of the time, but I admit there are days, like last week, when I am angry at the injustice of my brother’s life. Sometimes, I cry alone in my car for a few minutes before I can pull myself together and deal with the reality.

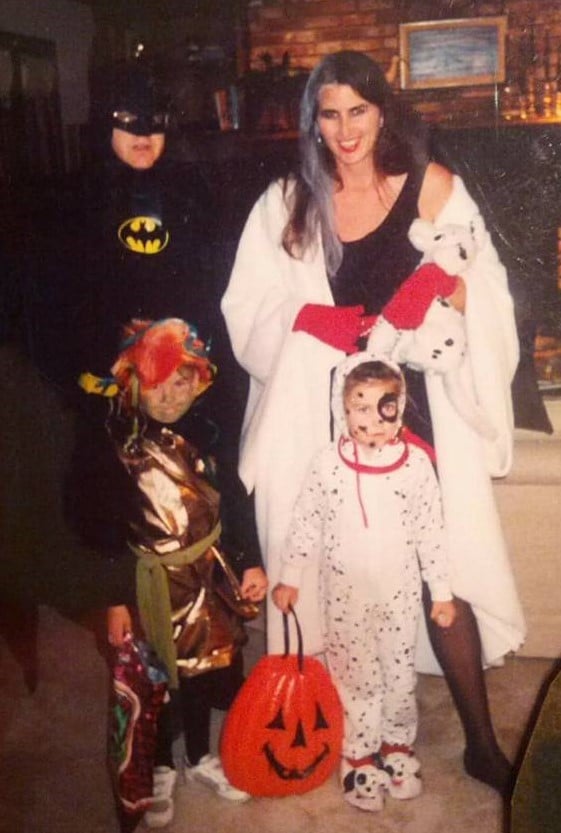

Our parents died many years ago, and my brother and I are now senior citizens. The discrepancy between my brother’s chronological and functional ages has widened to a deep chasm. It’s simultaneously sweet and heartbreaking when my brother chooses toys that are more age-appropriate for my three-year-old granddaughter. It seems plain wrong that my brother, who delights in Dr. Seuss books and stuffed animals, has thinning gray hair and a deeply wrinkled face. I try not to borrow trouble, but I’m painfully aware that people with intellectual disabilities tend to develop dementia ten years earlier than the general population. I worry, like my mom used to, that I will die before he does. A sister’s love differs from a mother’s love, but since my mother’s death, I’ve begun to understand her feelings about David in a way I didn’t before.

Life isn’t fair. Sometimes, we get dealt a challenging deck of cards, and no dealer is there to reshuffle. With every fiber of my being, I wish I could make the world a better place for my brother and everyone with disabilities or challenges. Someone recently posted that the children on the school bus frequently mock their child with disabilities, and I felt my heart breaking. Parents, please teach your children about compassion and kindness. Teach them about disabilities. Teach them about love and acceptance. It may be a difficult lesson to teach, but I promise it is easier than being the person on the receiving end of teasing, mocking, and cruelty.

Children learn from example. Parents, make sure your words and actions towards people who have disabilities reflect kindness and compassion. I can’t believe I still need to say this, but please don’t use the word “retarded” or any form of it in a derogatory manner. Children are always listening and watching. They want to be like their parents, so make sure you’re a person of character worth emulating.

The world wants to hear only the positive aspects of having a child with disabilities because it allows them to look the other way. Although it’s good to be optimistic, if we sugarcoat our experiences, it will enable society to assume we’re fine. If we’re fine, why should there be any motivation to change the world to accommodate people with disabilities? It allows lawmakers to deny legislation providing equal access to facilities and services. If we don’t speak up, we won’t get basic necessities such as family bathrooms with adult-sized changing tables or ramps so we can be out in the community. Only through advocating for our family members with disabilities do we get desperately needed services.

Of course, there are positive aspects. Never doubt that we deeply love our family members who have disabilities, but we need it to be acceptable to admit it can be challenging also. We need you to see us, we need you to include us, we need your kindness and compassion. We need you to vote for people who have the best interest of those with disabilities. If anyone needs a village, it is families who have a family member with disabilities. Life isn’t always fair, and sometimes it gets more difficult as the years pass. Or at least that’s my truth.

Welcome to Grand Life, the TulsaKids blog that explores the wonderful adventures of grandparenting! Join me and my grandchildren as we explore interesting activities and visit family friendly sites in Tulsa. This blog shares the joys and challenges of grandparenting as well as the various roles grandparents play in their grandchildren’s lives.

Welcome to Grand Life, the TulsaKids blog that explores the wonderful adventures of grandparenting! Join me and my grandchildren as we explore interesting activities and visit family friendly sites in Tulsa. This blog shares the joys and challenges of grandparenting as well as the various roles grandparents play in their grandchildren’s lives.