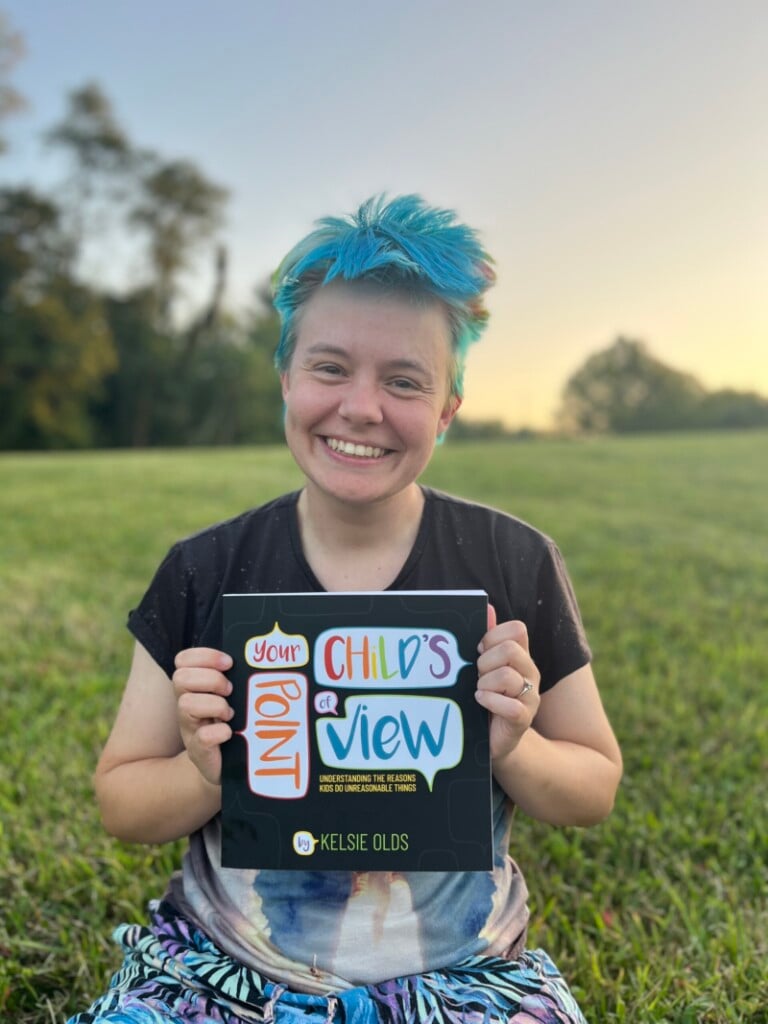

Your Child’s Point of View: An Interview with Kelsie Olds, The Occuplaytional Therapist

Author Kelsie Olds first became interested in occupational therapy at age 13, when family friends adopted a child with Down syndrome.

“I was 13 and newly allowed to use the internet, so I followed their blog,” Olds explains, which is where they first encountered the term occupational therapy. “And when I researched it, I was like, ‘That’s what I want to do with my life.’”

Pursuing this career brought Kelsie back to Tulsa in 2012 for college and grad school at ORU and OU-Tulsa. They worked in the area until 2020 in public schools, skilled nursing facilities and the Laura Dester Children’s Center in north Tulsa.

In 2021, after moving away from Tulsa, Olds started a Facebook page called The Occuplaytional Therapist, which has grown to over 160,000 followers. When they started the page, Olds says, “I was trying to post activities that you should do with your kids, and what they would be teaching them.” However, Olds’ approach has shifted since then, as they’ve continued to write and research. The page’s emphasis is now on child-led play.

“I think that adults often get in the way of kids when they decide, ‘We’re going to play this activity, and I hope that you’re going to learn this from it, and this will be your takeaway,’” Olds says.

Occupational Therapy and Play

Child-led play is central to Olds’ mindset as a pediatric occupational therapist. An occupational therapist is trained to address both physical and social/emotional difficulties. “OT is in the middle of a lot of Venn diagrams,” Olds says. “If there’s a very physical, bio-mechanical, medicine-based on one side, and then…people’s minds and people’s emotions on the other side, OT’s in the middle.”

OT differs from other types of therapy, Olds explains, because “it is rooted in what occupies your time. What’s meaningful to the person.” They give an example of two people recovering from wrist surgery: “An occupational therapist might find out that one has kids and loves knitting and needs to type on the computer all the time, and one is retired and likes to go fishing and doesn’t have anybody they have to take care of besides themselves. [The OT] might approach therapy differently with those two people because they’re rooting it in what’s meaningful to that person.”

When it comes to working with pediatric patients, Olds says, a primary difference is that the child isn’t the one who decided they needed therapy, rather, “it was a bunch of adults on behalf of the child.” And yet the child is the one who must show up for appointments and do the work.

“So the part of [OT] where it’s rooted in what’s meaningful to the person experiencing the therapy is absent if I come at it only from the lens of ‘I need to meet everything the adult said and please the adults’ – and leave the child out of the equation entirely. That’s not at all occupational therapy,” Olds says.

Using a child-led approach allows Olds to help the patient in a way that is meaningful to them, accomplishing therapy goals through activities the child enjoys. And what’s more, this approach is more effective than simply doing worksheets or exercises.

“[Children] play as naturally as they breathe,” Olds says. “And so, if I turn something into meaningful play, or give them an idea of a way to meaningfully play, then they’ll do it with their siblings and with their friends at recess and in the spare moments that they have at home…and I didn’t have to be like, ‘Here’s a bunch of assigned homework’ because I tapped into what’s magic about OT – it’s rooted in the meaning.”

Understanding Your Child’s Point of View

Olds says that people often comment that they have a knack for seeing things from a child’s point of view. And Olds has recently turned this gift into a book, Your Child’s Point of View: Understanding the Reasons Kids Do Unreasonable Things, to help parents develop this skill as well.

“I think that a lot of adults don’t remember what it’s like to be a child,” Olds says. Furthermore, “when people try to take a child’s perspective, I find that a lot of times they will get it wrong in ways that really reveal that the person might be thinking more about themself. Like, when a child is screaming and losing their mind, and the adult’s like, ‘They’re doing it to get attention from me,’ [when in reality] the child might just be losing their mind because they feel really bad.”

Your Child’s Point of View is divided into five main chapters: Babies and Toddlers, Littles and Middles, Tweens and Teens, At School and Inner Child. On the left-hand side of each spread are two word bubbles, one with an adult’s perspective on a challenging behavior, and one with “one possible child’s point of view.”

For example, in the Littles and Middles section, one adult’s point of view is, “She refuses to do simple things that she already knows how to do and insists she needs me to help her. She’s known how to do them for years. She doesn’t need my help.”

The possible child’s point of view states, “Please take care of me, even though I am big. Don’t expect me to do everything all by myself just because I physically can; I emotionally can’t.”

Beyond this, each scenario is accompanied by a page filled with relevant child development information, which can help adults realize when their expectations might not line up with a child’s abilities, and some problem-solving activities adults can try when the situation arises.

Although the book can’t cover every possible situation, Olds hopes that adults can take the general concepts and create a framework from which they’re able to work through other challenging scenarios.

Sensory Processing

A concept that comes up throughout the book is sensory processing. “Sensory processing is the way in which people take input from the world through their senses, which includes the five senses that you learned about in school, but also other ones like your sense of balance, your sense of movement, being able to interpret your inner body sensations – like hunger, the need to go to the toilet, things like that,” Olds explains. “And turning it into something meaningful or actionable or what you need to be able to function at the best level that you can.”

There are four sensory processing styles that affect how people react in different situations. “Some people need a lot of sensory input in order to be able to regulate their body,” Olds says. “And some people get overwhelmed by too much sensory input and need ways to filter some of it out.”

A child more prone to being overwhelmed by sensory input may get upset over loud noises, unexpected or uncomfortable sensations, etc. A child who generally needs more sensory input may tend to wiggle, fidget, and so on.

“It’s not that having a sensory processing style is dysfunctional or anything like that,” Olds says. “But if you’re at the very extremes of them, you could be seeing impacts on your day-to-day life. You could be having a harder time getting your needs met.”

At these extremes, seeing an OT might help a child learn to function in a healthier way. “But if it’s just one or two ‘annoying’ things that your child is doing…then coming at it from a sensory lens of problem solving might help,” Olds says. “You might be able to realize, ‘Oh, they’re probably not making a lot of noise all the time to annoy me, they’re making a lot of noise all the time because they want to hear the sound of something. Maybe we could play music in the house.’”

Caring for Your Inner Child

Your Child’s Point of View can not only help parents and caretakers relate to children in a more understanding way, it can also help adults find more compassion for themselves and prioritize making sure their own needs are met.

“There’s a huge component where [an adult reader] might be like, ‘Nobody ever saw me this way. Nobody ever afforded me this grace,’” Olds explains. “Nobody ever told me about my brain and the way it processes things. How am I supposed to do that for another human being? I don’t even know how to do it for me!

It takes time to override the messaging that you might have heard from adults growing up,” Olds continues, “so there’s a whole section about your inner child because I’m also trying to convey how to take care of yourself and how to balance this. No part of the book is supposed to be like, ‘Adults are wrong, kids are right, get over yourself.’ None of that would ever be any messaging that I would hope to convey. It’s like, ‘We’re a team. The team has a bunch of different needs depending on how big it is. And we all need to get our needs met. Nobody’s needs are more important than somebody else’s needs…And that takes a lot of figuring out, and it’s very hard, and it’s also possible. That’s what I hope to convey.”

Follow Kelsie Olds on Facebook and Instagram: @occuplaytional, or visit their website, occuplaytional.com, for additional resources. Your Child’s Point of View: Understanding the Reasons Kids do Unreasonable Things is available on Amazon.